I’ll retain the name Chromatin as long as Chemistry has decided about it, and I empirically refer to it as that substance in the cell's nucleus which takes up the dye upon staining the nucleus ("Kerntinktionen").

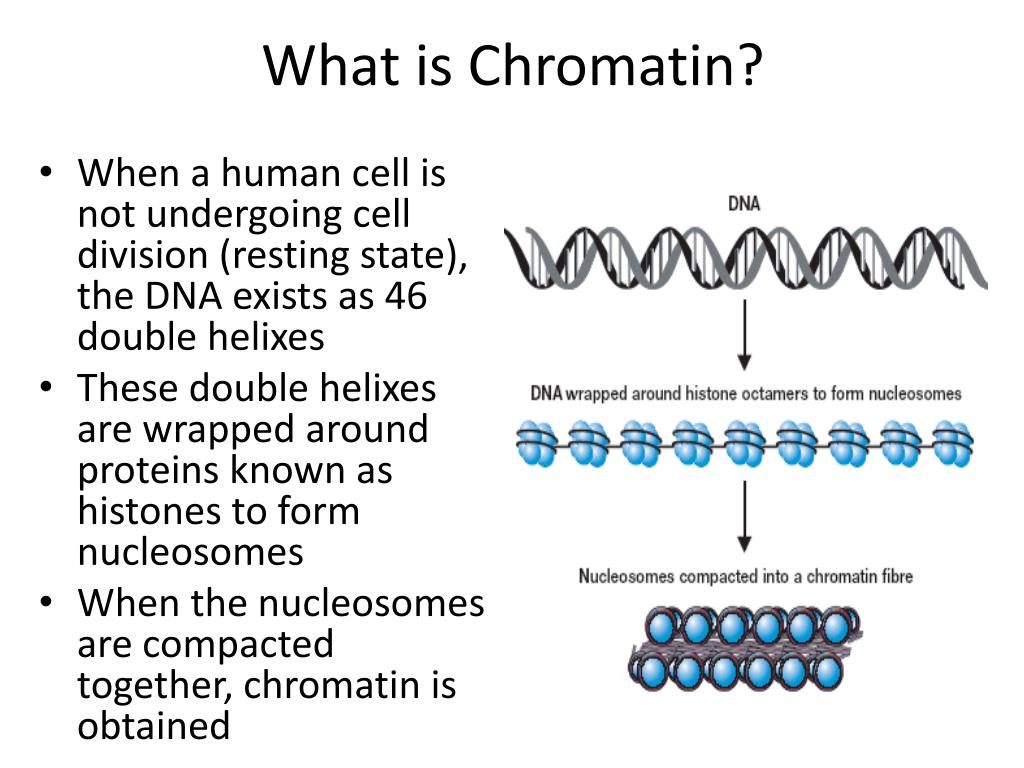

It is possible that this substance is really identical with the Nuclein-bodies. from German): “The scaffold owes its capability of refraction, the way how it behaves, and in particular its colorability to a substance which, with regard to its latter attribute, I have termed Chromatin. Furthermore, there were nucleoli, the nuclear plasm and the nuclear membranes. Flemming assumed that within the nucleus there was some kind of nuclear-scaffold. In 1882 Walther Flemming used the term chromatin for the first time. The changes in structure are required to allow the DNA to be used and managed, whilst minimising the risk of damage. The structure of chromatin varies considerably as the cell progresses through the cell cycle. Recent evidence however, has revealed that these traditional fixed views of chromatin are not strictly correct and that both active and inactive genes can be found within chromatin regions of either type. These correspond to uncompacted actively transcribed DNA and compacted untranscribed DNA. In non-dividing cells there are two types of chromatin: euchromatin and heterochromatin. The different levels of chromatin compaction are clearly visible in cells. These structures do not occur in all eukaryotic cells there are examples of more extreme packaging, for example spermatozoa and avian red blood cells.

WikiProject Molecular and Cellular Biology may be able to help recruit one. This article or section is in need of attention from an expert on the subject.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)